2.2

Russia’s wartime economy hits its ceiling

Share:

20.12.2024

Eesti keelesRussia’s economic momentum is slowing, with the "wartime economy boom" likely to end in 2025, significantly increasing the risk of nasty surprises, such as budget revenue shortfalls.

In the short term, a regime-threatening economic crisis is unlikely without external shocks, as the authoritarian government can fund its war machine by diverting resources from other sectors.

Since late 2022, Russia’s economy has been on a wartime footing, moving steadily along an uncertain path to an unknown destination. Military spending in the federal budget has reached record levels year after year, with nearly 18 trillion roubles allocated for defence and internal security in 2025, amounting to 40% of the federal budget.

Production capacities that stood idle before the war have been reactivated with federal funding, but the low-hanging fruit has been picked.

However, there are clear signs that the surge in military-industrial output, driven by federal funding, has reached its limit. Even Russia’s official statistics indicate that industrial production volumes in monetary terms have plateaued since September 2023, fluctuating by a few per cent in either direction month-to-month. Considering inflation of around 10%, actual output has either stagnated or even slightly declined. It appears that underutilised and idle production capacities have been brought online with federal funding, but the low-hanging fruit has been picked. Further increases in production volumes sufficient to create a macroeconomic impact would require substantial new investments in industrial capacity, which is a much more complex and time-consuming effort. Notably, only a few highly prioritised sectors, such as drone manufacturing, have seen substantial new capacity created.

Russia’s budget revenues have been robust in 2024. While the high domestic tax revenues were expected due to the infusion of wartime spending into the economy, the more than 1.5-fold increase in oil and gas revenues compared with the previous year came as a surprise – even to the Russian government. Global oil prices remained high due to OPEC+ agreements, and Russia managed to bypass Western-imposed price caps with the help of a shadow fleet and intermediaries. The price of URALS crude oil occasionally reached $80 per barrel, about a third above the price cap and higher than government forecasts.

THE CENTRAL BANK’S IMPOSSIBLE TASK

Russia’s central bank finds itself in a bind. Inflation is running at more than twice, and sometimes even three times, the bank’s target rate. To combat this, the central bank has continued to hike its base interest rate, which has reached 21% with no end to the cycle in sight. This rate hike has significantly worsened prospects for sectors not tied to military procurement but has had little impact on the defence industry, which benefits from preferential loans. Consequently, the central bank faces an impossible task: to control inflation without being able to address its primary source.

In November 2024, the Russian rouble hit a new low against the dollar

Source: Maxim Shipenkov/EPA

Russian consumer sentiment ignored the war early in the year, with optimism peaking in spring before starting to cool slightly. Spending levels remain high, and Russian consumers have accumulated substantial savings, enabling them to sustain their spending habits for some time, even during more challenging periods.

The multi-year property boom in Russian cities is likely coming to an end.

Interesting trends have emerged in the property sector. In July 2024, the government ended most programmes offering subsidised mortgage rates for new housing. As a result, homebuyers now face mortgage interest rates exceeding 20% annually. This change led to a sharp decline in transaction volumes, though the full impact will take time to materialise, as previously agreed deals under earlier terms are still being finalised. The multi-year property boom in Russian cities is likely at an end, marking the collapse of a key pillar of economic growth and consumer confidence. As a result, the construction sector will face a significant surplus of workers, which may, figuratively speaking, shift labour from “cement mixers to the meat grinder” – driving increased mobilisation for the war in Ukraine.

SANCTIONS BITE HARDER

While Russia managed to mitigate the impact of oil price caps, other sanctions have significantly affected its economy. Third-party countries, including China, have begun restricting transactions with Russia out of fear of secondary US sanctions, complicating Russia’s foreign trade and raising transaction costs. The Moscow Stock Exchange can no longer trade in Western currencies due to sanctions, making it impossible to determine their actual market value. This allows Russian banks to manipulate currency rates at the expense of clients, which substantially increases the costs of export and import transactions in Western currencies for Russian companies. Russia’s “wartime economy boom” is likely to end in 2025, increasing the risk of negative surprises, such as budget revenue shortfalls. However, the economy retains significant inertia, making a sudden downturn unlikely without external shocks, although the overall trend is clearly downward. A potential negative shock could stem from a worse-than-expected performance of China’s economy or the collapse of OPEC+ oil production limits, which would sharply reduce global oil prices and, by the same token, Russia’s oil and gas revenues.

A special operation over medical operations

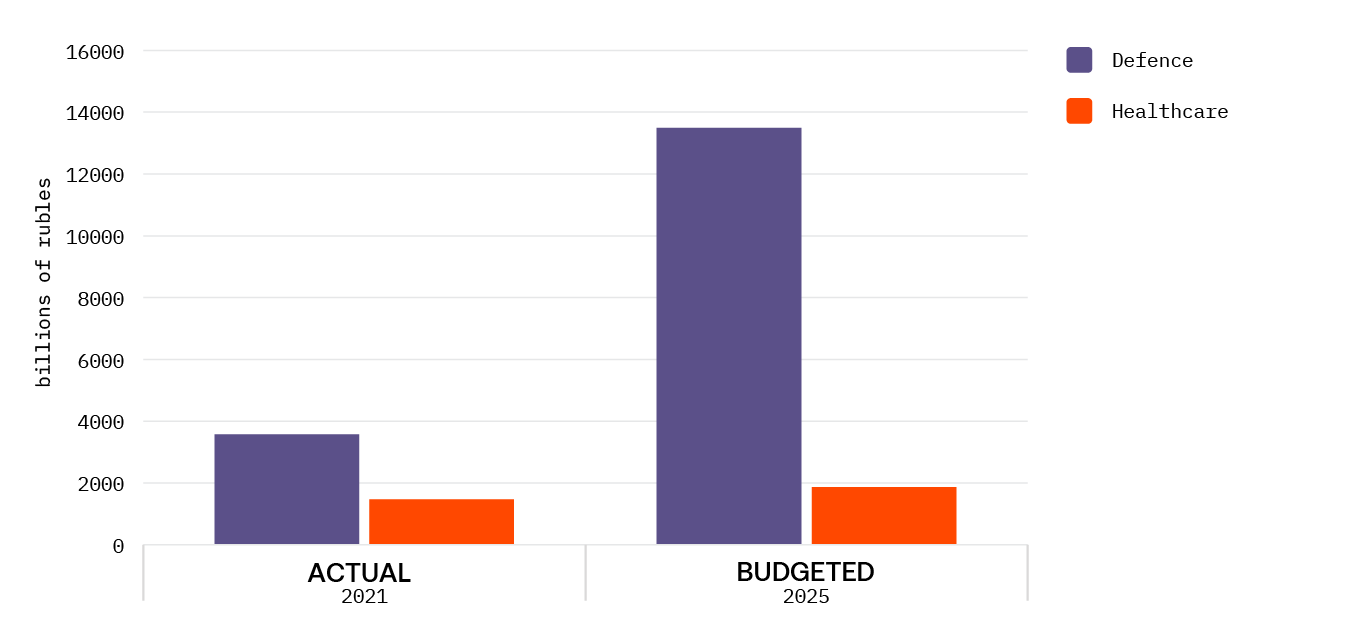

Before the full-scale war in Ukraine, Russia spent 2.4 times more on national defence than on healthcare. In the 2025 budget, defence spending is projected to be 7.3 times higher than healthcare spending.

Share:

20.12.2024

Eesti keeles