2.2

‘War and Peace’ – the Nobel Peace Prize, Russian-style

Share:

The Kremlin hopes to polish its international reputation through covert influence efforts.

Russia recognises the limits of relying on its influence agents in the West and has shifted the focus of its efforts towards third countries.

Marginalised from most Western political and cultural circles, Russia has responded by creating its own international peace prize on its own terms.

Excluded from the top tier of international politics, Russia has spent recent years pursuing various reputation-management initiatives to reshape its image as an aggressor state.

One such initiative emerged in December 2021, when the chairman of the Russian Historical Society and director of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), Sergey Naryshkin, together with Vladimir Medinsky, a presidential adviser and chair of the Russian Military-Historical Society, decided to create an alternative to the Nobel Peace Prize. Together with Leonid Slutsky, chair of the State Duma International Affairs Committee, they established a foundation to award what amounts to a parallel-world peace prize – the L. N. Tolstoy International Peace Prize.

Named after an icon of Russian literature and a committed pacifist, the peace prize was designed to recognise individuals, organisations or initiatives for achievements that contribute to “security based on the rule of international law” and to building a “multipolar and nonviolent world”.

The foundation appointed as its director Doku Gapurovich Zavgayev, a former Russian ambassador to Slovenia. Among his earlier exploits was organising, in 2019 and under the guidance of the Russian Historical Society and Naryshkin, a ceremony to light an Eternal Flame in Ljubljana – in what the Kremlin triumphantly proclaimed at the time as “the heart of NATO”.

‘POSITIVE ENGAGEMENT’

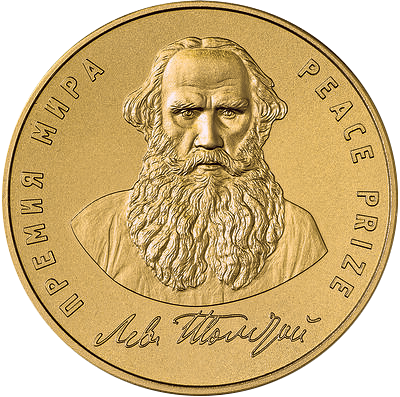

The first Leo Tolstoy Peace Prize was awarded to the African Union. At a gala ceremony held on 9 September 2024 at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre, the prize was presented by the jury chair, conductor and director of the Bolshoi Theatre, Valery Gergiev. Moussa Faki Mahamat, chair of the African Union Commission, accepted the diploma and gold medal bearing Tolstoy’s portrait. The monetary award amounted to 30 million roubles, or just over 300,000 euros.

Signing of the founding protocol of the Leo Tolstoy International Peace Prize Foundation at the Victory Museum in Moscow on 22 June 2022 (from left in the front row: Konstantin Mogilevsky, Leonid Slutsky, Viktor Martynyuk; from left in the back row: Sergey Naryshkin, Vladimir Medinsky). Source: peacefound.ru

Awarding the prize to the African Union was primarily motivated by straightforward foreign policy calculus. The Kremlin recognised the need to shore up its position in Africa, where Russian commercial interests were experiencing setbacks. African states account for roughly a quarter of the votes in the UN General Assembly. To “positively engage” these nations, the organisers of the award ceremony sought financial backing from Russian companies with business interests on the continent, such as Uralchem, Uralkali and Acron.

CAUTION TOWARDS THE WEST

In 2025, the prize was awarded to the presidents of the Central Asian states of Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. This immediately created a dilemma regarding the location and manner of the award presentation should all three presidents have been prepared to accept it. The original plan had been to hold the award ceremony in Dushanbe, but the leaders of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan might have seen this as assigning greater weight to Tajikistan. As a compromise, the ceremony took place at the informal summit of leaders of the Commonwealth of Independent States in December.

The Central Asian nominees were not the only contenders last year. Three Members of the European Parliament – Michael von der Schulenburg, Ondřej Dostál and Ľuboš Blaha, who also attended Moscow’s 9 May celebrations – nominated the well-known economist Jeffrey Sachs. The jury’s vice-chair, Pierre de Gaulle (Charles de Gaulle’s grandson), acknowledged Sachs’s contribution to “promoting a multilateral world order” but regarded the border agreement reached between the Central Asian states as the more deserving achievement.

From the outset, the Kremlin was wary of awarding the prize to Western candidates. When the 2024 prize was being prepared, it became clear that finding a suitable Western nominee would be rather challenging. Several names proposed by members of the foundation’s leadership – such as Roger Waters, a founding member of the rock group Pink Floyd, film director Oliver Stone, or former German chancellor Gerhard Schröder – were deemed respectable but potentially counterproductive by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In Waters’s case, officials were uncertain whether he would agree to accept the award or travel to Moscow. As for Stone and Schröder, the ministry noted the “Russophobic predisposition” of their home countries and concluded that awarding them the prize would not resonate positively there from Moscow’s perspective.

SUPPORT FROM DMITRIEV

The ostensibly noble peace prize is nothing more than another active measure by the Kremlin, orchestrated with the involvement of the special services.

To secure a sponsor commensurate with the initiative, the founders of the Tolstoy Peace Prize approached Kirill Dmitriev, who heads the Russian Direct Investment Fund, asking him to support the 2025 ceremony and the foundation’s activities with 15 million roubles. In the view of the foundation’s organisers, the prize would help reinforce Russia’s position on the world stage and foster business and economic ties between domestic and foreign companies. Dmitriev himself had been conspicuous the previous year for his involvement in the Ukraine ceasefire talks, and efforts to restore business ties with the West are hardly unfamiliar to him.

As becomes clear on closer inspection, this ostensibly noble peace prize is nothing more than another active measure by the Kremlin. It has been orchestrated with the involvement of Russian special services, aiming to manipulate well-meaning foreigners to advance Russia’s foreign-policy objectives.

The Kremlin is acutely aware of the utility of its “protégés” and deploys them deliberately to serve its objectives. Anyone approached to take part in a Russian “positive engagement” initiative should therefore treat such invitations with caution and consider how their participation might be instrumentalised.

Share: