3.3

Russia’s economy faces only bad options

Russia’s economy has entered a downturn.

The defence sector is expanding at the expense of a contracting civilian economy.

A complete collapse of the Russian economy remains highly unlikely.

The year 2025 is likely to be remembered in Russian economic history as a pivotal moment. Expectations for a sustainable war economy have shifted to debates about the inevitability, pace and severity of an economic downturn.

This shift towards deterioration occurred steadily, without major shocks, yet with striking consistency. By autumn, for example, Russian manufacturing firms perceived the business climate as markedly worse than it was at the height of the initial wartime turmoil in spring 2022.

This is not merely a matter of sentiment; clear indicators, including a sharp slowdown in fixed-capital investment in the first half of 2025, support this. Low productivity caused by outdated technology is one of the Russian economy’s structural weaknesses.

Sanctions-related restrictions have exacerbated this problem. Declining investment means that neither technological upgrading nor the associated productivity gains can be expected, either in the short or the long term. Sanctions have had a clear and substantial impact on Russia’s economy. Measures targeting the financial sector have been particularly effective, cutting Russia off from international capital markets. Consequently, the government is forced to finance its budget deficit domestically, incurring borrowing costs that are much higher than Russia’s relatively low public debt level would otherwise imply.

Low energy prices and a strong rouble have dampened Russia’s foreign trade to such an extent that it no longer contributes meaningfully to economic growth. The current-account surplus, which reached 77 billion US dollars in the second quarter of 2022 and helped absorb the initial shock of sanctions, fell to just 17 billion dollars in the same period of 2025, a nearly fivefold decline.

Nearly all sectors of Russia’s domestic civilian economy have either already entered recession or are struggling at the brink of one. In this situation, the only source of demand growth comes from military spending financed by an already overstretched state budget. Even that demand, however, is far from sufficient to sustain the economy as a whole. Rapid growth is confined primarily to ammunition, precision-weapons production and sectors associated with electronic warfare and drones. The rest of the defence industry is following the civilian sector with a lag of one to two years, suggesting that production volumes in the military-industrial complex are also likely to stagnate in 2026.

In 2026, Russia’s GDP is likely to contract, increasing the risk of economic and social instability. Both inflationary and deflationary recession scenarios are possible, with the decision largely resting on the Russian government. A positive scenario is no longer achievable: even with a swift end to the war and the removal of sanctions, Russia will still face serious economic difficulties. While an economic crisis is a possibility, a total collapse of the Russian economy remains highly unlikely. A more plausible outcome is that financial considerations will carry much greater weight in political decision-making than before.

THE FEDERAL BUDGET AS A RITUAL OF NECESSITY

For several years, Russia’s federal budget has been drafted and presented, despite its having little relation to reality.

During 2025 alone, the budget was amended twice, with revisions so extensive that the original core parameters were changed beyond recognition. By September, the deficit had grown almost fivefold compared with the initial projection. This drastic increase was driven by wartime spending that had spiralled out of control and revenues that fell nearly 10% short of expectations.

There is little reason to assume that officials at Russia’s Ministry of Finance are incompetent. Far more likely, the budget’s core framework is shaped by a political brief that, during wartime, does not permit the inclusion of unpopular figures in a widely circulated official document. Reality enters the budget only gradually, through successive “amendments” that receive far less media attention than the original version. Meanwhile, State Duma deputies, officials and analysts continue to discuss the budget’s official “priorities” and “focus areas” with straight faces, exactly as the ritual requires.

Leaving aside oil and gas revenues, the core parameters of the draft budget for 2026 are likewise closer to the absurd than to the realistic. They, too, will highly likely be substantially revised over the course of the year.

Key parameters of the 2025 federal budget

PUTIN IN RESTRUCTURING MODE

In early September, President Vladimir Putin visited the ODK–Kuznetsov aircraft- and rocketengine plant in Samara. The plant belongs to the United Engine Corporation (ODK), which in turn is part of Rostec, Russia’s largest defence-industrial conglomerate. During his visit, Putin commended the achievements of the domestic industry, noting that Russia ranks among the world’s five leading producers of aircraft engines. He also highlighted increases in output achieved over the past four years. According to Putin, the sector’s “positive momentum” is fostering the conditions needed to secure Russia’s industrial and technological sovereignty.

At the same time, the very same plant is subject to a “financial recovery programme” within the ODK group, which essentially means it is being restructured. Nearly half of ODK’s subsidiaries are in a similar position. The budget guidelines for 2026 explicitly prohibit any investment or expenditure that is not strictly necessary to fulfil existing state defence contracts.

The deteriorating financial health of Russia’s defence industry is further reflected in extensive chains of arrears, with companies owing large sums to suppliers while waiting for payments from their own customers. Long-term contracts that were signed in earlier years are now loss-making due to sharp price increases. Additionally, interest rates on working-capital loans available on market terms are exceeding 20% per year.

OIL PRODUCTION FALLS AMID A LACK OF INVESTMENT

Since the onset of the full-scale war in Ukraine, Russia’s crude oil production has experienced a year-on-year decline. Moscow could previously attribute this to production caps imposed under the OPEC+ framework from 2022 to 2024, but that justification is no longer valid. In 2025, despite the lifting of those limits, there was no expected rebound in crude output; however, gas condensate production continued to rise.

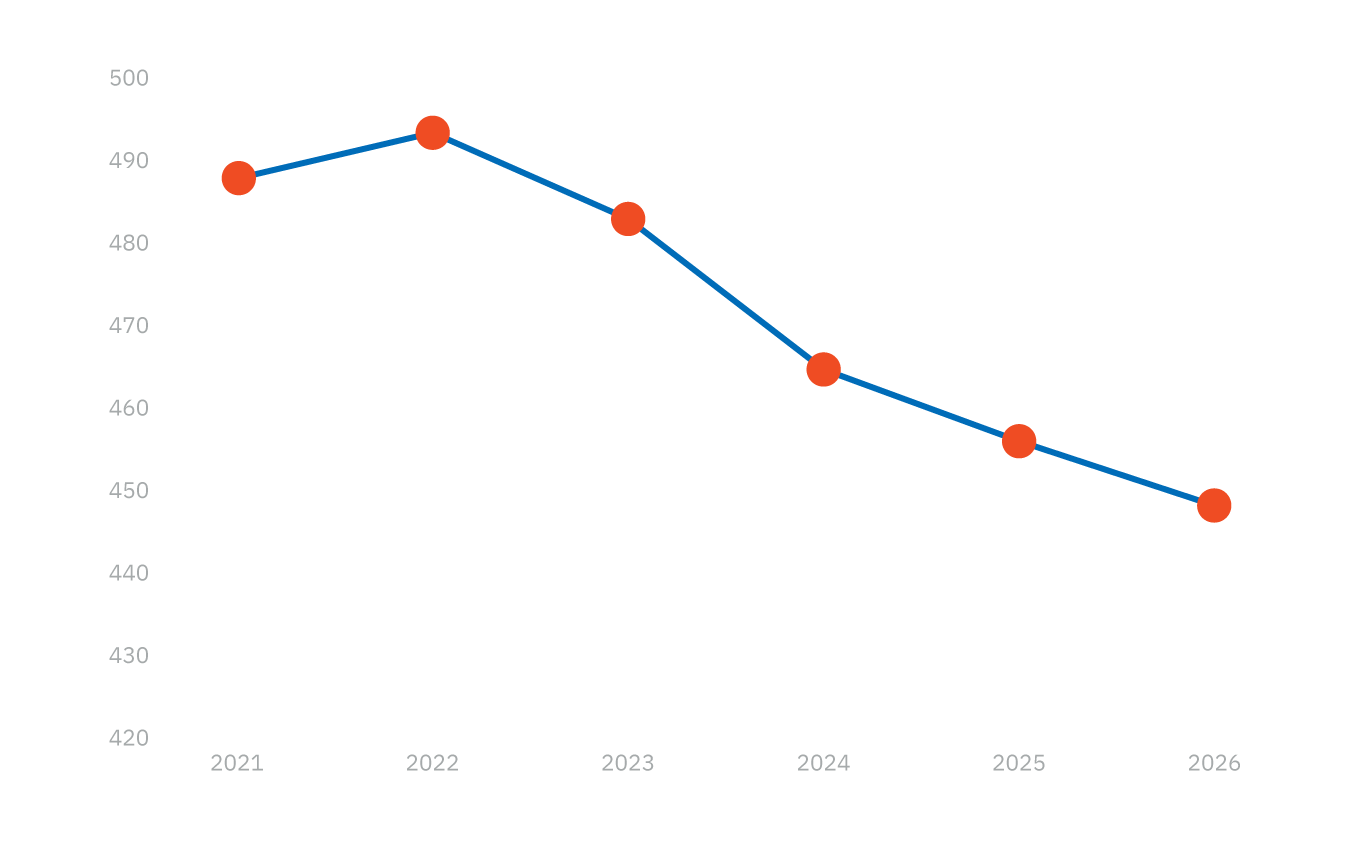

Russia’s crude oil production, 2021-2025, with a forecast for 2026 (million tonnes)

The primary driver of the decline in oil production is the deterioration of the resource base. In mature fields, wells are increasingly flooded with groundwater, and easily accessible reserves in Western Siberia are being depleted. Additionally, investment aimed at maintaining production levels has decreased and become less profitable.

A second – and no less important – factor is the sanctions that restrict access to Western technology. Without imported equipment and expertise, Russia is unable to tap hard-to-reach reserves or improve efficiency at existing fields. As a result, these technology sanctions increase the likelihood of stagnation in the oil sector.

Lower oil prices, a stronger rouble and a higher tax burden further constrain investment in crude oil production. While profits accounted for around 15% of sales revenue for Russian oil companies between 2022 and 2024, this figure decreased by roughly half in 2025.

As a consequence of declining investment, an increase in crude oil production is unlikely in the coming years. As in previous years, overall output is being sustained by higher gas condensate production. Given these circumstances, Russian oil companies are unlikely to earn higher profits in 2026 than last year; in fact, profits are likely to decline further.