4.1

GRU involvement in importing dual-use goods

Russia’s military-industrial complex, strained by sanctions, continues to function thanks to Kremlin intermediaries who keep dual-use goods flowing into the country.

Russia’s military intelligence service plays an active role both in identifying procurement needs and in acquiring sanctioned goods from abroad.

Moscow’s efforts to circumvent sanctions require closer cooperation among Western security and law-enforcement authorities and the modernisation of Western legal frameworks.

Since March 2022, when it became evident that Russia’s plan to seize Ukraine within a few days had failed, the country’s military-industrial complex has faced significant pressure. It is responsible for supplying the armed forces with sufficient materiel to maintain an advantage on the battlefield.

Russia’s military industry is facing significant challenges due to a lack of essential inputs, including raw materials, microelectronics and medical equipment. Even basic components are typically imported because domestic production fails to meet military industry standards. To acquire the critical goods needed from abroad, Russia has mobilised all government bodies that engage with the outside world, including its intelligence services.

SANCTIONS AND EVASION EFFORTS

The sanctions imposed to slow Russia’s war machine have created numerous problems for Moscow. The most painful restrictions have affected the semiconductor, mechanical engineering and aviation component sectors.

Putin’s regime is actively adapting to sanctions, continually devising new methods to circumvent them. To conceal the end-user, additional intermediaries are introduced into the procurement chain, and goods are repackaged to hide their origin. Shipments are routed through countries in the Far East, the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa, while organised crime networks are also exploited. Russia increasingly relies on friendly states, such as China, Iran and even India, utilising them as producers and intermediaries.

Autonomous production that is not reliant on foreign components will not be achievable in Russia’s military industry for the foreseeable future. Therefore, we can expect even greater efforts to circumvent sanctions.

THE GRU’S ROLE IN RUSSIA’S PROCUREMENT SYSTEM

The main task of the GRU is to obtain the military, political, economic, defence, and scientific and technical intelligence that the leadership of Russia requires for decisionmaking. In addition to collecting intelligence, Russia’s military intelligence service also conducts influence operations. One of its objectives is to support the country’s economic development, scientific and technological progress, and military-technical capabilities. Consequently, the GRU plays a significant role in facilitating the flow of sanctioned goods into Russia.

The GRU is not the only organisation involved in evading sanctions, but its advantages in this field are clear. Intelligence officers receive training that equips them with a thorough understanding of Western technology, proficiency in foreign languages, and the ability to approach targets while concealing their true intentions. Many GRU officers who focus on procurement have spent extended periods posted in target countries as diplomats or trade representatives. However, sanctions evasion is far from the glamorous work associated with Cold War espionage. While GRU officers once focused on obtaining samples of adversaries’ technological breakthroughs and bringing them home, today, roughly a hundred military intelligence officers spend their working days handling product codes, price quotes and logistics chains.

Since the 1990s, GRU officers have established import–export companies in Russia to source goods from abroad. Although the trade officers of these GRU front companies still travelled relatively freely within the Schengen area after the annexation of Crimea, such travel has declined sharply since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

To compensate for the loss of direct access to producers, Russia has pursued several strategies. These include forming new joint ventures with local businessmen abroad, leveraging existing networks and international trade fairs to make new contacts, and cultivating relationships with foreign partners and managers of Russian logistics firms to involve them in schemes aimed at evading sanctions.

GRU chief Igor Kostyukov during a defence-cooperation visit to India, July 2024. Also pictured are senior GRU officers Aleksandr Nazarenko and Aleksandr Zorin. Source: Indian Armed Forces

Because the GRU is directly involved in identifying Russia’s military-industry procurement needs and available suppliers, procurement officers sometimes inflate prices for personal gain – for example, to fund a comfortable stay in a desirable destination such as Hong Kong.

NEPTUN KO LTD

Founded in Moscow in 1996, Neptun Ko Ltd (ООО Нептун Ко Лтд) initially described itself on its website a few years ago as an import–export company operating in Russia, the Commonwealth of Independent States, the European Union, and Southeast Asia. The products offered included mechanical-engineering components, diagnostic instruments, and electronics and IT equipment. Its clients reportedly included Russian security authorities, research institutions and major industrial enterprises, such as Rosatom, Rosneft and Lukoil, as well as banks.

Aleksandr Matrosov.

However, today all references to Russia have disappeared from the website. It now claims to be the Egyptian company N.E.S.T. (Neptune for Engineering Services & Technology), stating its mission is to connect “some of the world’s leading contractors, suppliers and traders”. Despite this rebranding, Russian registries, invoices, and correspondence confirm that Neptun Ko remains registered in Russia. Since 2008, Aleksandr Matrosov has served as its director general, and has been identified as a GRU officer. Matrosov is only one of at least ten GRU officers we have identified among Neptun Ko’s current or former senior personnel (see the list in the textbox).

IDENTIFIED GRU OFFICERS

Koshkin Ruslan Petrovich, born 7 August 1951

Votchenko Aleksandr Filippovich, born 12 April 1955

Sazhin Nikolay Nikolayevich, born 1 January 1957

Mazurik Sergey Nikolayevich, born 2 September 1960

Matrosov Aleksandr Vasilyevich, born 15 September 1960

Gaivoronskiy Roman Viktorovich, born 19 September 1979

Zubkov Dmitriy Yegorovich, born 29 May 1979

Popov Stanislav Sergeyevich, born 25 October 1979

Strafilov Konstantin Aleksandrovich, born 30 June 1983

Mamontov Maksim Yuryevich, born 16 August 1984

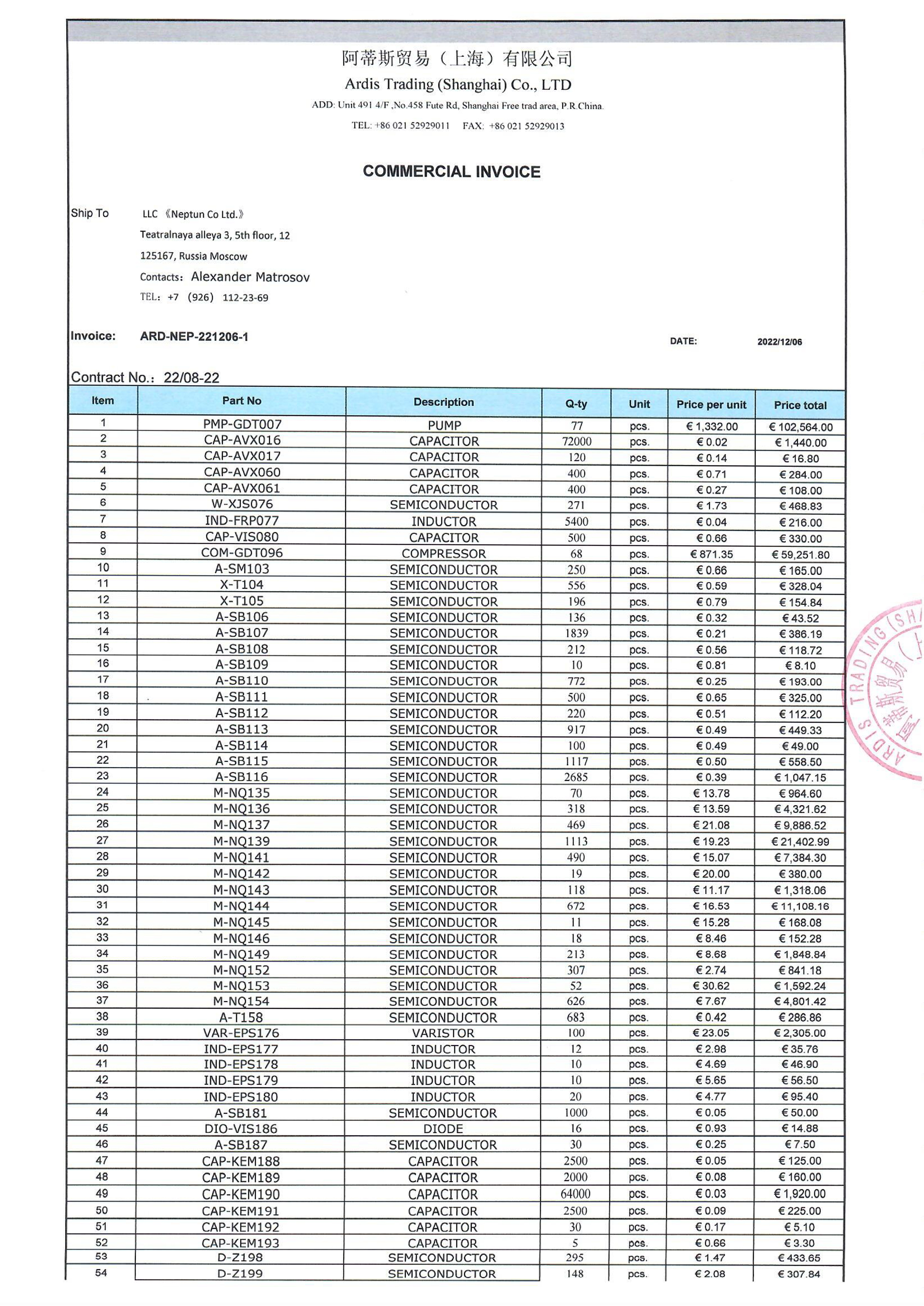

In recent years, Neptun has specialised in procuring microelectronics and laboratory equipment through countries in Southeast Asia and the Far East. For instance, during the first year of the full-scale war in Ukraine, Matrosov obtained more than 500,000 euros worth of critically important semiconductors and other components for Russia’s military-industrial complex through the Chinese supplier Ardis Trading (see the invoice on p. 51).

Neptun’s other partner in China is Shine Resource (Qingdao) Co., Ltd. This company has helped Neptun in shipping machinery made by the US company Quaser and the Chinese manufacturer Bosunman to Russia.

The GRU not only imports goods to Russia but also markets Russian products in friendly foreign states. For example, Ruslan Koshkin, who is linked to Neptun, is active in the association MNPA IS (МНПА «Инновационные системы»). The president of this association is Valentin Korabelnikov, who was dismissed from his position as a GRU chief in 2009. In 2020, Korabelnikov and Koshkin sought to convince Eurasian Economic Commission board member Sergey Glazyev to promote Russian exports to Guatemala. It remains unclear whether the corruption charges brought against Korabelnikov in 2021 were related to the same deal.

According to a representative of one ecosystem firm, a GRU officer in his sixties named Vladimir Vladimirovich (the representative either did not know or did not wish to provide his surname) admitted that he had become morally exhausted by the grim nature of his work in a difficult global environment. Although officially retired, he is compelled to continue working, and even business trips to destinations like Thailand and Dubai offer him no relief.

Ever-tougher sanctions, the demanding nature of the work, a shortage of recruits, and complaints from end customers about delays and poor-quality goods are taking their toll even on hardened intelligence officers. In addition, the loss of a former key incentive – the opportunity to travel to Western Europe – makes the frustrations of GRU procurement officers understandable.

COUNTERMEASURES

Companies that managed Russia’s transit links with the West and Asia, both before and after the war began, require careful scrutiny.

Countering sanctions evasion requires more than simply sanctioning the companies involved in these networks. Neptun Ko is undoubtedly not the only firm supplying Western components to Russia’s military industry. The links in the procurement chain are relatively easy to replace, as there are still individuals in the West and elsewhere who are willing to participate in Kremlin schemes for personal gain. Companies that managed Russia’s transit links with the West and Asia, both before and after the war began, require careful scrutiny. More effective countermeasures should address the entire process, not just isolated parts. In addition to scrutinising supply chains, end users and financial flows, particular attention should be paid to the organisers of sanctions evasion, including Russian intelligence officers. The number of such “experts” in Russia is limited. Rather than solely sanctioning shell companies, it may be more effective to publicly expose the professional shell creators behind them.

Investigative journalism can also make a significant contribution in uncovering schemes that violate sanctions. Unlike intelligence and law enforcement agencies, journalists often find it easier to bring information on sanctioned procurement practices into the public domain. For instance, the Ukrainian channel Telebachennia Toronto conducted an in-depth investigation into the GRU-linked company Neptun Ko mentioned above. These revelations help raise awareness among various audiences, including producers of dual-use goods, as Western manufacturers do not want to find themselves publicly linked to GRU officers and their networks.

Screenshot from a Telebachennia Toronto video on Neptun Ko Ltd. Source: Телебачення Торонто Youtube channel

In addition to journalism and intelligence services, law-enforcement and legislative bodies must also adjust to the current situation. If involvement in sanctions-evasion networks were considered a criminal offence in allied countries, law-enforcement agencies would not need to spend additional resources proving links to Russian intelligence services. Updating existing legal frameworks and coordinating with partners are undoubtedly major undertakings. Still, we need not look far back for a positive example: in the recent decade, the fight against terrorism showed how Europe and NATO, with their partners, were able to swiftly develop effective measures for information-sharing and disruption, which have significantly reduced the threat of terrorism in Europe today.