7.2

Risk assessment is key to protecting classified information

Estonia’s framework of measures for protecting classified information is largely uniform and allows for little flexibility at the level of individual institutions.

Risk management must be continuous, as risk assessments become outdated quickly.

Protection measures should therefore be determined on a risk basis at the points where information is created and processed, to enable timely responses to threats and support international cooperation.

States classify their sensitive information to protect it from potential adversaries or the public, as its release may threaten national security, international relations or other vital interests.

The greatest threat to the security of classified information comes from hostile states that seek sensitive material from Estonia and its allies. These states aim to strengthen and protect their own military capabilities, geopolitical influence and strategic positions. Authoritarian countries often utilise sensitive foreign information to conduct political influence operations both domestically and internationally. Additionally, industrial espionage, or the theft of sensitive technology, is becoming more common and is particularly valuable to states subject to international sanctions.

For Estonia, the main threat comes from hostile states in our neighbourhood. More distant hostile states may also attempt to exploit Estonia as a gateway for gaining access to sensitive information belonging to our allies and about countries they view as adversaries or potential adversaries. Terrorist organisations likewise pose a threat, as they may be interested in Estonia’s critical infrastructure and security measures for the purpose of planning attacks.

Sensitive information must be safeguarded against both external and internal threats. Employees may leak information in exchange for monetary gain or personal favours, or for ideological reasons. Hostile intelligence services seek to recruit individuals with access to valuable information, making anyone in such a position a potential target. Therefore, access to sensitive information is always restricted on a need-to-know basis, and individuals must undergo a background check or security vetting before receiving clearance.

HOW SHOULD THREATS TO CLASSIFIED INFORMATION BE ADDRESSED?

Information varies in sensitivity, and it is not always feasible or practical to protect it in the same manner. Information can be a strategic resource whose reliability, integrity and availability must be ensured, as these factors underpin the state’s ability to respond to threats. International information sharing and mutual trust are equally important; therefore protection must be secure, flexible and up to date.

Western countries largely follow a risk-based model to safeguard classified information. This means that the need for protection is evaluated when information is created, and the appropriate protection measures are determined when it is processed, taking into account its intended use.

This resembles practices in the private sector, where companies decide how to protect their sensitive information – personal data and trade secrets, including sensitive technologies and other intellectual property – based on the risks arising from threats.

Risk-based protection is most firmly established in highly regulated sectors where leaks may result in financial losses or state-imposed penalties, including finance, high technology, critical infrastructure, digital services and cybersecurity, pharmaceuticals, healthcare and the defence industry.

Estonia, however, has assigned risk-based decision-making to the legislature and the government. Consequently, institutions responsible for creating and handling classified information can influence the choice of classification levels and protection measures only to a limited extent. Estonia also needs to grasp the modern principle of risk-based protection – both to cooperate effectively with allies and the defence industry, and to develop future safeguards for its classified information.

HOW ARE CLASSIFICATION LEVELS SET ON A RISK BASIS?

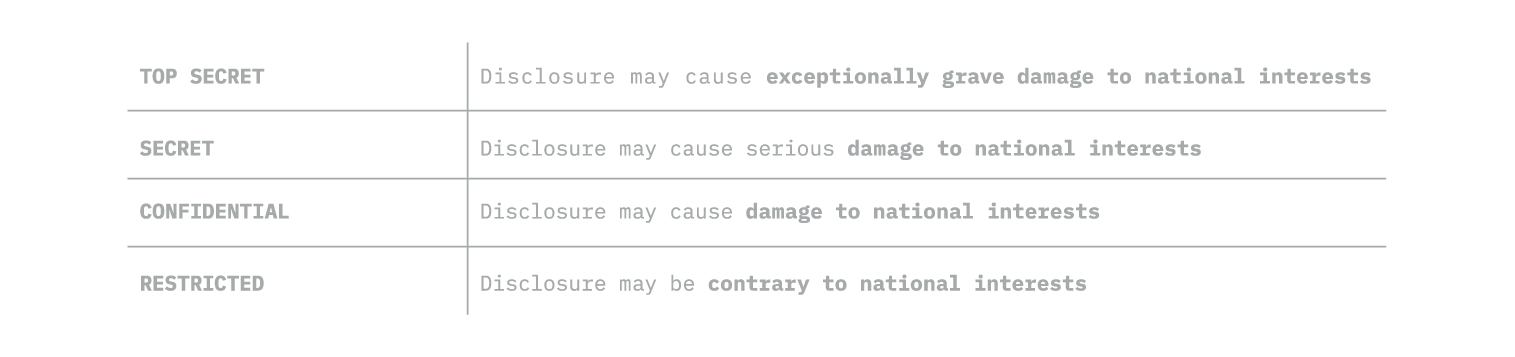

Western countries generally define the levels of classified information by the extent of damage that could result if the information were disclosed to someone without authorised access. A typical definition of classification levels is as follows:

As a rule, the institution that generates the information is authorised to classify it, as it is best placed to analyse and identify the risks associated with that information. The responsible institution evaluates the overall risk and assigns an appropriate classification level and duration to each category of information. National guidelines for classification are often advisory or not publicly available, as threat and risk assessments may themselves contain sensitive information.

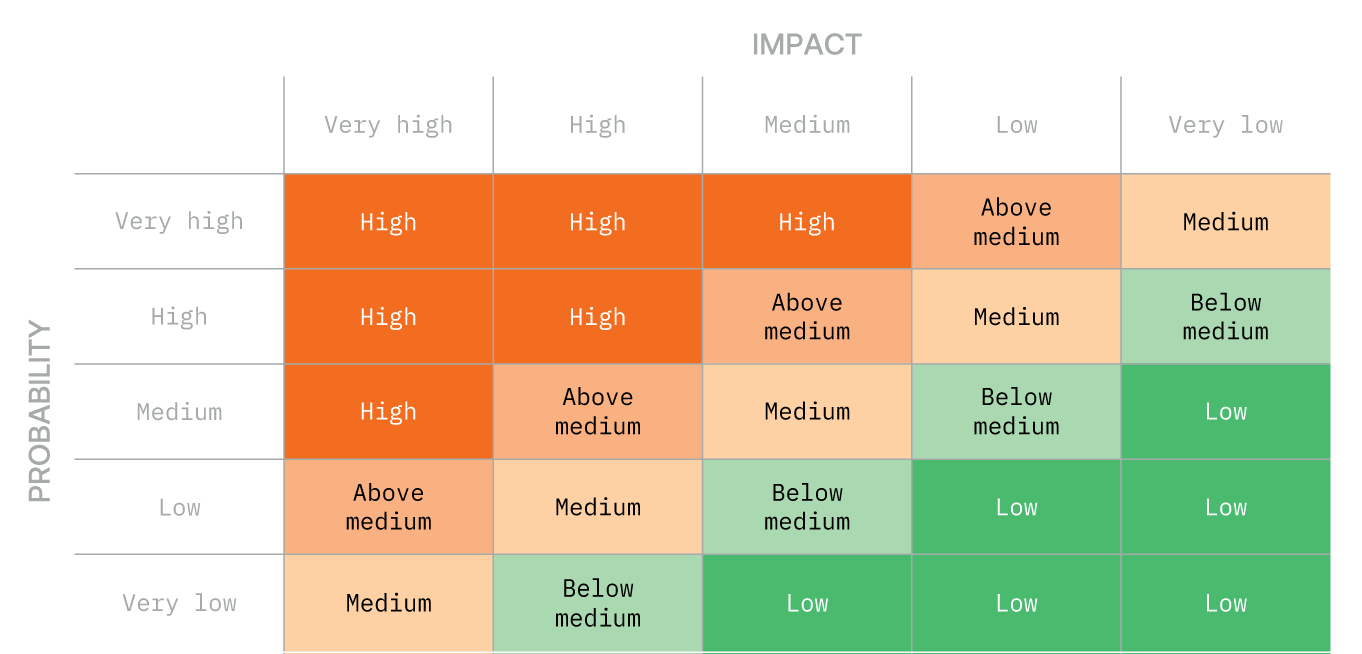

One method used in risk analysis is a risk matrix, which helps assess risks by considering the likelihood of a threat materialising and the impact of a leak. Depending on the context, the likelihood and impact may be determined either through precise calculation or through another form of assessment.

In Estonia, too, classification levels depend on the need for protection, and in certain limited cases, some flexibility is allowed regarding the classification level or duration. Under specific conditions, additional exceptions are permitted in electronic information security (cybersecurity), allowing information to be classified at a lower level than otherwise required.

However, in most cases, the categories of information subject to classification, as well as the level and duration of classification, are defined by law. For example, according to Estonian law, information may be classified only if it concerns international relations, national defence, the maintenance of law and order and security authorities or infrastructure – a narrower scope than that used in most Western states. The law largely sets out very detailed grounds for classification, which at times means the wording does not cover all sensitive information, preventing such data from being classified.

While this approach provides some clarity on the grounds for classification, in practice, institutions that create information often struggle to adapt flexibly to changing needs. They might find it challenging to determine which sensitive information requires classification, or whether it should be classified at a higher or lower level, or how long it should remain classified. Changes at the legislative or regulatory level can be time-consuming and require coordination nationwide, making the process too slow and restrictive to address rapidly evolving needs.

HOW ARE RISK-BASED PROTECTIVE MEASURES DETERMINED?

Protective measures for classified information must account for hostile actors’ interests and opportunities to gain access, including situations involving large volumes of information or cases where classified material is handled outside a secure environment. Electronic processing requires rigorous risk assessment, given that hostile states conduct cyber operations to access Estonia’s sensitive information and that cyber espionage is difficult to detect.

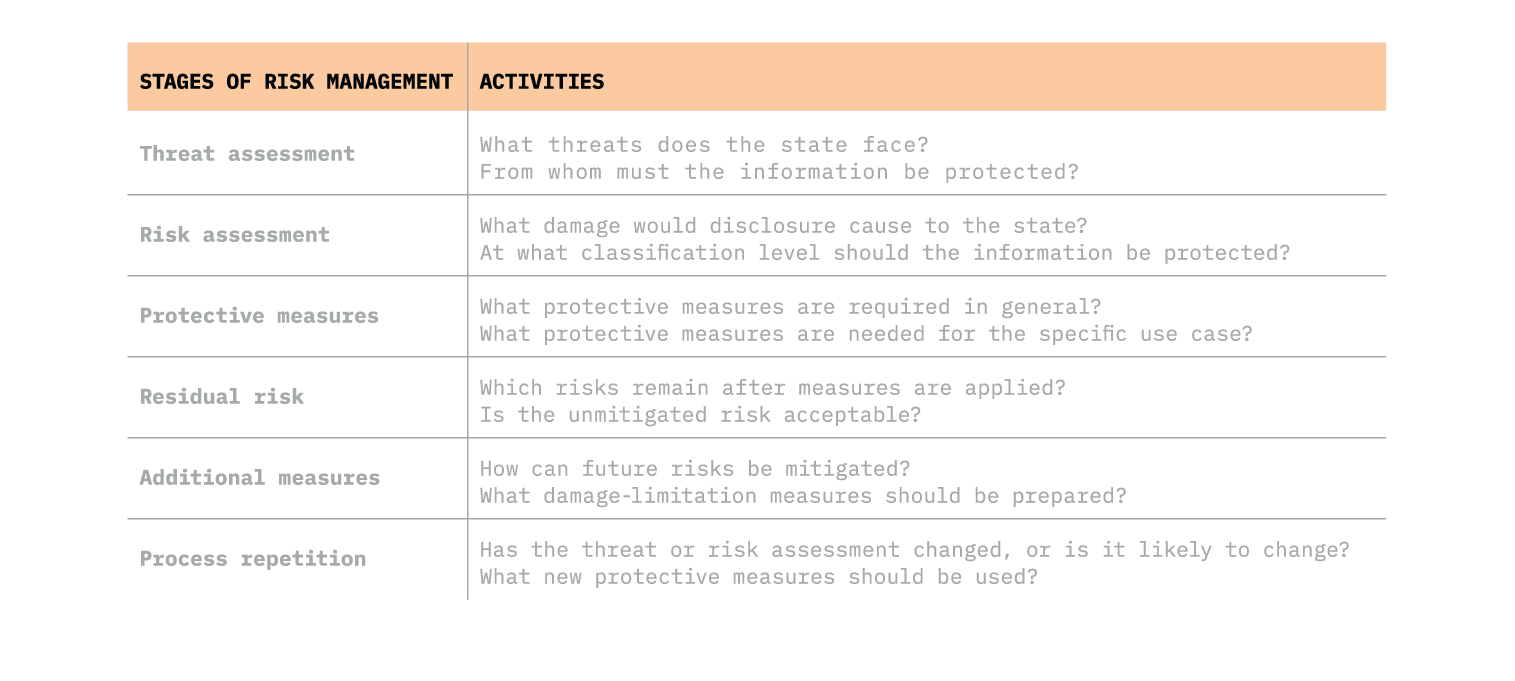

In Western countries, only the minimum requirements for protecting classified information are generally set at the state level. At the same time, each institution is expected to determine, based on its risk assessment, which specific protective measures to apply in a given case. The process of assessing risks and mitigating them through protective measures is known as risk management.

There will always remain some risk when protecting classified information, and the creator of the information must decide whether the identified residual risk is acceptable and whether the institution is prepared to tolerate it. It is also important to recognise that an institution’s risk tolerance level may shift in a crisis, and the legal framework should allow it to make different decisions in such circumstances. The final stage of risk management involves preparing additional measures to mitigate future risks – for example, those arising from technological developments, as well as establishing damage-limitation procedures for situations where information can no longer be protected.

In Estonia, the protective measures applied to classified information are generally uniform, offering limited flexibility. Greater consideration is given to lower-level, risk-based protective measures in electronic information security, where systems containing classified information must undergo continuous risk management. In general, however, little consideration is given to the fact that institutions have very different operational needs or may face different threats when protecting their classified information.

While this uniform approach provides nationwide clarity, the lack of flexibility may hinder the adoption of new technological solutions, which would be easier to introduce initially at the level of individual institutions. It is also difficult to regulate new solutions nationally when no institution has experience using them.

The inflexibility also hinders cooperation with allies whose systems for protecting classified information already allow some risk-based flexibility, while Estonian institutions are required to apply uniform protective measures. As a result, obstacles arise in joint exercises and operations, in the deployment of shared systems, and in international procurement.

A risk assessment begins to lose its relevance the moment it is completed, which is why risk management must be a continuous process. The benefit of this approach is that the creator and custodian of the information must regularly reassess the threats the information must be protected against, the level of protection required and the measures needed to address them. Introducing a risk-based approach at institutions that create and process information may initially seem like a significant departure from established principles. However, in practice, this approach would enable a more flexible use of classified information when necessary, while ensuring it is protected with the most up-to-date safeguards.