5.3

The moral decline of Russian armed forces

Russia employs a wide range of methods to meet its recruitment targets: physical force, deception, intimidation and psychological pressure are applied to enlist soldiers when financial incentives are insufficient.

Lawlessness, abuse of power, corruption, theft, alcoholism and drug use are widespread in Russia’s armed forces. Crime originating within the armed forces poses a threat to both Russian society and neighbouring states.

The Kremlin lacks effective mechanisms to reintegrate military veterans into society.

The Russian authorities have established a nationwide system for recruiting new soldiers to offset massive losses on the Ukrainian front. Responsibility for filling the ranks of the armed forces rests primarily with Russia’s regional governments, which are required at all costs to meet monthly and annual recruitment targets set by the Ministry of Defence.

As the number of volunteers continues to decline, local administrations have resorted to increasingly drastic measures to meet these quotas. On the one hand, recruits are lured by unprecedented financial incentives; on the other, they are subjected to intense pressure to sign service contracts. Media reports indicate that physical force, deception, intimidation and psychological manipulation are frequently used in the recruitment process.

Cynical recruitment efforts particularly focus on socially vulnerable groups.

Cynical recruitment efforts particularly focus on socially vulnerable groups, including the unemployed, chronic debtors, detainees, individuals under judicial supervision, those suffering from alcohol or drug addiction, as well as labour migrants and others. Consequently, Russia’s frontline units are largely composed of individuals who, under normal circumstances, should not be entrusted with weapons.

Lawlessness, abuse of power, corruption, theft, alcoholism and drug use are widespread in Russia’s armed forces. Frontline soldiers also frequently commit serious crimes against civilians. Additionally, reports are increasingly emerging of illegal trafficking in weapons taken from the battlefield, which are likely to end up in the hands of criminal networks.

‘THE NEW ELITE’

Although official narratives portray frontline soldiers primarily as heroes and as Russia’s “new elite”, the public is well aware, mainly through social media, of widespread abuses committed by soldiers both within the military and in civilian life. Rather than addressing these underlying issues, authorities seek to suppress the flow of information through repressive measures. As a result, the term “new elite”, which has been promoted by Putin, has become a target of bitter sarcasm among the Russian population. Consequently, returning soldiers are increasingly met with fear and caution. A survey conducted by the Levada Centre in autumn 2025 revealed that 39% of Russians anticipate a rise in crime linked to the return of war veterans. Additionally, half of those surveyed either did not wish to express an opinion or did not dare to do so.

Recently, some Russian officials have been forced to acknowledge that the mass recruitment of individuals with criminal backgrounds for the war in Ukraine has led to a sharp increase in crime, and that this issue is likely to worsen once the fighting ends. A study published by the Ural State Law Institute of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs notes that the highest-risk group consists of individuals convicted of serious violent crimes who received pardons upon recruitment into the armed forces. According to the study, their return to civilian life after the war will be particularly difficult, and a large proportion are likely to revert to criminal activity.

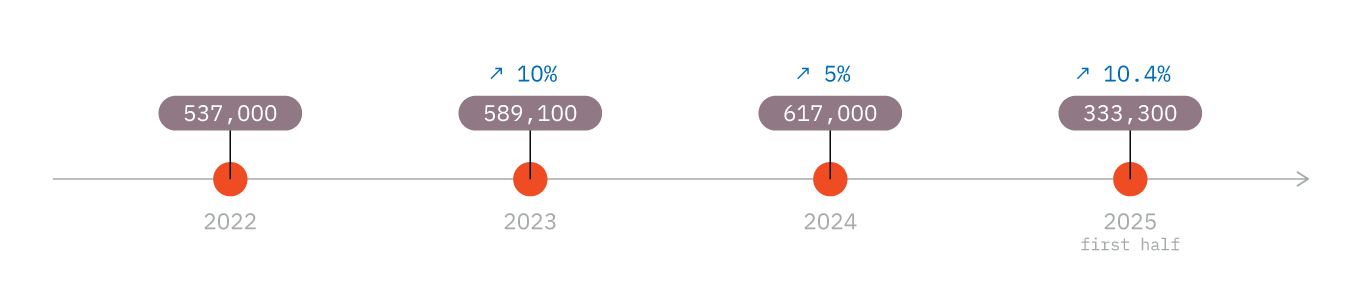

Statistics for serious and particularly serious crimes, according to the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs

According to Russian investigators, between 150,000 and 200,000 convicted criminals were recruited from prisons to the front between 2022 and 2025. How many of them have since been killed or demobilised remains unknown. Official statistics indicate that at the beginning of 2022 there were 465,000 inmates in Russian detention facilities; by October 2023, this number had fallen to 266,000. At the beginning of 2025, Russia reportedly held around 313,000 prisoners.

The return of military veterans to civilian life is likely to be accompanied by a rise in crime.

This risk does not concern Russia alone, and Western states must also factor in additional threats:

• the spread of organised crime originating in Russia

• the expansion of illegal trafficking in weapons and explosives

• the spread of terrorism and extremism

• the return of foreign nationals who fought in the war back to their home countries

In light of these risks, it is important to maintain additional travel restrictions and enhanced background checks for visa applications originating from Russia, even after the end of the full-scale war. This will also help prevent Russian war criminals from entering Europe.

VETERANS AS A THREAT TO INTERNAL STABILITY

From the perspective of the Russian Presidential Administration, crime originating within the armed forces primarily poses a threat to the regime’s domestic political stability, and this risk could increase significantly with the end of the war and demobilisation.

The regime must reckon with the fact that most men returning from the front will no longer earn incomes comparable to their military pay, which could sow the seeds of politically charged discontent. Additional strain on the social welfare system is also inevitable: the state must contend with large numbers of severely wounded veterans and with widespread addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems.

The government lacks the financial resources to implement large-scale rehabilitation programmes.

The Kremlin is therefore preparing to prevent the emergence of “uncontrolled” veterans’ organisations and political movements. To mitigate these risks, the Presidential Administration has launched nationwide programmes to reintegrate veterans into society. Regions are also required to take measures to ensure veterans’ employment and medical rehabilitation.

The federal training programme ‘Time of Heroes’ is intended to create the impression that frontline soldiers returning from the war will enjoy excellent career opportunities in state and local government. In reality, participation in the programme is limited to a small number of carefully vetted servicemen. Moreover, a significant share of these positions is held by officials who served near the front but did not participate in combat operations.

The Russian government lacks the financial resources to implement large-scale rehabilitation programmes. Years of chronic underfunding have significantly weakened the country’s social welfare system, leading to an acute shortage of medical personnel, particularly specialists in mental health. Consequently, when the war ends, the vast majority of veterans are likely to be left to cope with their problems alone, which will inevitably result in rising social tensions.

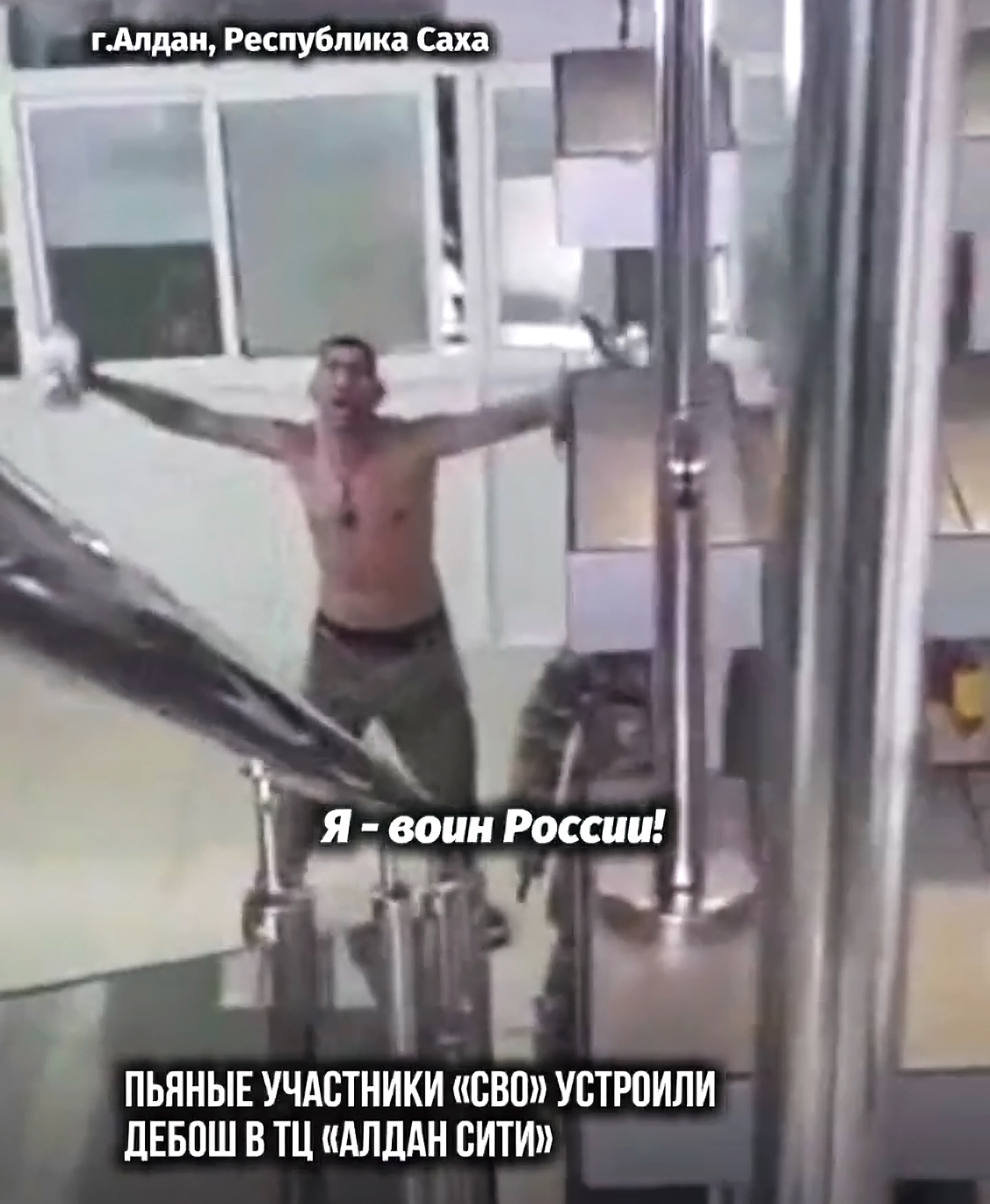

An intoxicated “special military operation” veteran assaulted people at a shopping centre in Aldan, Yakutia. “I am a Russian warrior!” he shouted amid the abuse. Source: screenshot